- How to

- 30 July, 2021

Want to ride 100 miles? Master 50 Trek-Segafredo Head of Performance Josu Larrazabal explains how to know when you're ready for a century

Hello! This is Part 2 of a series detailing my journey to ride my first century as part of the Trek 100 in August. Here’s Part 1 explaining who I am.

The Trek 100 raises money for the MACC Fund, which is fighting to end childhood cancer and related blood disorders. You should DONATE TO MY RIDE or even just DONATE DIRECTLY TO THE MACC FUND. Either way your money goes to the same great cause.

Now onto the content.

As I write this, I’m 27 days out from the Trek 100 and my first century. Even as someone who had been doing shorter rides somewhat regularly, that’s … not a lot of time. I would not be attempting 100 miles if not for several coworkers who assured me that it’s doable. Riding 100 miles is cycling’s rough endurance equivalent of running a marathon, but because it puts less impact strain on the joints and muscles, it’s a little easier to prepare on short notice.

My biggest question was, “How will I know I’m ready?” His answer: “When you can ride 50 really well.”

So I can do it. How is another matter. I am not a savvy sportsman in any regard. I’ve been winging my diet and exercise for all of my 33 years, rarely with an actual goal in mind. (I ran a half marathon once. Four years ago.) I’ve never gone for a ride that I didn’t know was comfortably within my bounds, or required more preparation than freshly inflated tires and a pocket of snacks.

This mission to ride 100 miles might have died on the vine if not for one thing: I work for an intricate, world-class racing operation, giving me uncommon access to some of the very best athletes, coaches and trainers that the sport has to offer.

Small detail, that.

So I reached out to Trek-Segafredo’s Head of Performance Josu Larrazabal and told him my goal. And although he was coming off a torrential three weeks helping the men’s team navigate the Tour de France, he graciously answered all of my questions about how to prepare for my first century.

My biggest question was, “How will I know I’m ready?” His answer: “When you can ride 50 really well.” Let Larrazabal explain:

If you can do half the distance well, you can eke out the full distance … just be aware that you won’t be setting any records.

Larrazabal explains exercise as a series of stimuli. You give your body a stimulus, it creates fatigue, and the body responds with an adaptation. Repeat this process frequently enough and you can overhaul your fitness level through a series of little adaptations. Larrazabal says that aiming to work out every other day — seven times for every two-week span — is a good target for those trying to train around their work, family and social lives. Less than that, and progress could be slow.

“If there is not enough continuity of the stimulus, you will not be able to create a training adaptation,” Larrazabal says. “During the week when you have work, if you do one-and-a-half and two-hour rides, and then on the weekend do a couple longer rides between three and four hours, then it’s enough to start preparing something.”

Note that Larrazabal’s advice is geared towards simply completing a 100-mile ride. Riding it with speed would require a more intense and nuanced training plan that is well outside my purview. Instead, I have one simple mission, Larrazabal says: Ride 50 miles “under control.”

What does that mean?

You give your body a stimulus, it creates fatigue, and the body responds with an adaptation.

“In my case, let’s say I start training when I’m completely out of shape, and I can ride my bike 21 or 22 kilometers per hour on average [roughly 13 MPH],” Larrazabal says. “Later, when I get some level, I can do it at 25-26 KPH [15.5-16 MPH]. At that moment when you are able to increase your speed for that half distance, you will have the range to reduce that pace and go longer on the bike. You can slow the pace and do the total distance.”

Larrazabal also stresses that the only way to be fully confident about completing 100 miles on the day of the event is to do a 100-mile ride in training. Barring that, the farther I can go in a single ride comfortably — whether that’s two-thirds or three-quarters of the full distance — the better. Still, “that half distance reference is enough,” he says. “But it’ll still for sure be a challenge.”

Why is 50 miles our target?

Larrazabal points out that marathoners rarely train by regularly running 26.2 miles. They do shorter, speedier chunks.

“How many marathons do the guys do during the season? Maximum two,” Larrazabal says. “And they don’t train doing marathons every week even at easier paces. They do one hour, they do a lot of half marathons, but never they go for the full piece.”

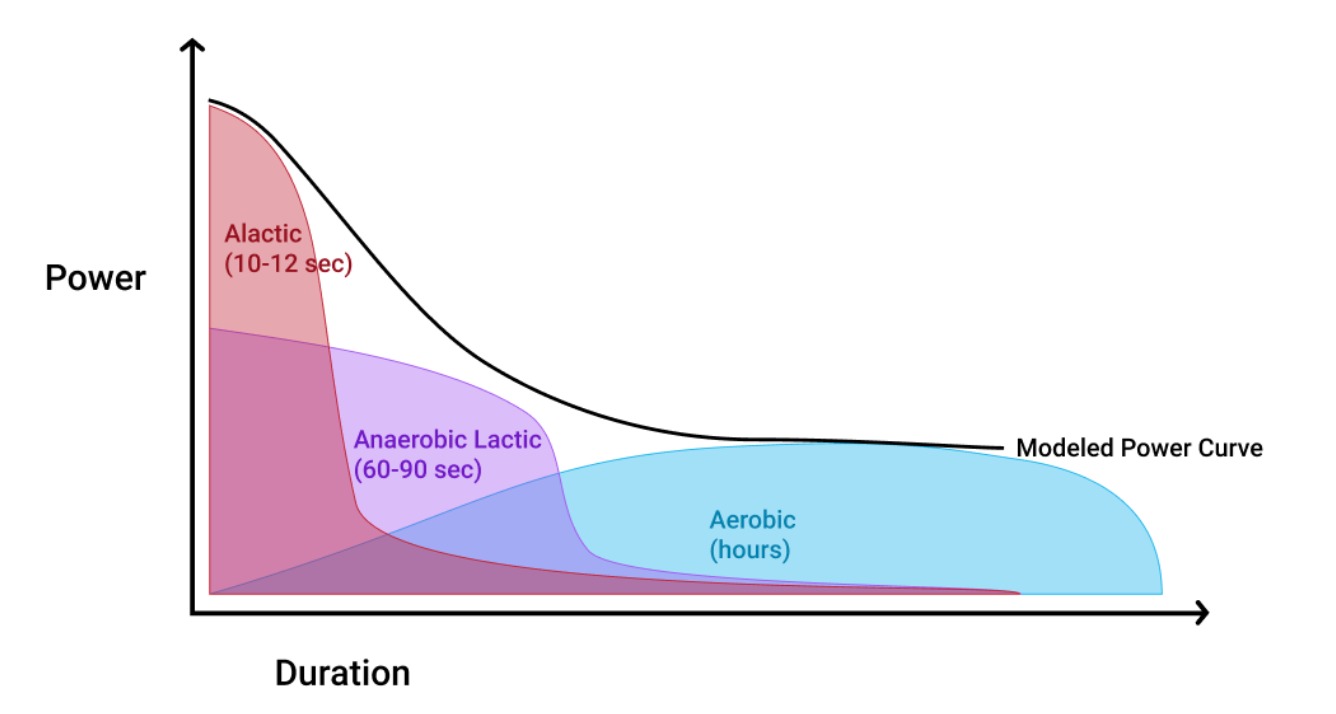

The reason is the chart below, which displays the energy systems used by the body during exercise. During a 100-mile bike ride, the body relies on the aerobic system, which works primarily off of the body’s long-burning fats and carbohydrates, and reduces the influence of the alactic and anaerobic lactic systems, which primarily rely on fast-acting stores of glucose to accomplish short, intensive bouts of exercise.

The reason is the above chart, which displays the energy systems used by the body during exercise. During a 100-mile bike ride, the body relies on the aerobic system, which works primarily off of the body’s long-burning fats and carbohydrates, and reduces the influence of the alactic and anaerobic lactic systems, which primarily rely on fast-acting stores of glucose to accomplish short, intensive bouts of exercise.

“Fat is a very efficient energy,” Larrazabal explains. “It gives a lot of calories for every unit. It gives that energy in a really slow way [compared to glucose], but it’s really efficient, so you can take a lot of energy from that.”

Notice in the chart that the power produced by the aerobic system doesn’t decline for a long time once it takes over. According to Larrazabal, depleting the aerobic system is very difficult, even for an average athlete. More often, their body’s mechanical systems — their joints, muscles and skeleton — suffer fatigue and pain before their endurance gives out.

You can feel pretty good about your chances of completing 100 miles after doing 50 miles because both tasks engage your aerobic system, and your aerobic system is really good at its job.

“When you do an exercise that relies on your fats [like long distance cycling], you can go for hours,” Larrazabal says. “You stop earlier because you have pain in the back, or pain in the feet, or you have saddle pain, or some other mechanical issue.”

If you’re feeling lost, here’s the point: You can feel pretty good about your chances of completing 100 miles after doing 50 miles because both tasks engage your aerobic system, and your aerobic system is really good at its job. You might not be able to do 100 miles at the same pace as your half distance effort, but again, speed isn’t the point. We’re just trying to get across the finish line.

“‘100 miles I want to do it,’ I think this is the base description where we should start. And I think it’s something that applies to 90 percent of the people,” Larrazabal says. “And I think it’s interesting to talk about these things because it applies to 90 percent of the people. So if someone wants to talk about being professional and has all the time to train, that’s fine, that’s nice, but it’s not realistic or applicable to many riders.

Pay special attention to your “mechanical fatigue.”

Some good news: “Cycling is not traumatic,” Larrazabal says.

I.e., the body isn’t making impact with the ground, so the physiological stress being placed on the joints and muscles isn’t as severe as it can be with running.

But that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t be careful about overextending yourself. Bike positioning can put strain on the skeleton, especially if you aren’t acclimated to long days in the saddle, or haven’t been properly fitted. You should pay attention to any lower back or neck pain in particular, and rest or make adjustments to your bike as needed.

Fortunately, there’s some more good news: Every minute on the saddle counts. Even shorts rides — those mid-week jaunts whenever you have a spare 30 minutes or more — add up.

Every minute on the saddle counts. Even shorts rides — those mid-week jaunts whenever you have a spare 30 minutes or more — add up.

“Even if you don’t do five- or six-hour rides, but you do many one- or two-hour rides, your body will get used to it,” Larrazabal says. “Your core muscles will get stronger, you will keep the position in the saddle more stable, and you will be able to cope with that fatigue.”

One of the biggest risks of a 100-mile ride, Larrazabal warns, is losing form to put more power into tiring legs. The hips and lower back move out of position to put more weight and muscle into stamping the pedals, potentially causing a host of minor discomforts that become major pains after several dozen miles.

Building an aerobic base will combat those issues, as will proper pacing. To maintain good positioning late in a long ride, it’s important not to go out too hard and expend the energy needed to ride comfortably at a good speed in the closing miles.

Managing the day of the race is vital.

Seriously, MAKE SURE YOU’VE PLANNED YOUR RIDE.

Poor planning can undo months of preparation. The Trek 100 website has a good list of tips for the big day. Larrazabal went into further detail with three important pieces of advice:

Tip 1: “Don’t get empty” — “The first risk is to empty yourself, to finish in a flat situation. Depending on the way it comes, with the brain running only on sugar, sometimes when the sugar flat goes too deep you can feel dizzy. It’s not nice when you are descending a climb.

“We should not need gels, like fast sugars. We should be able to eat normal energy bars, or even some fruits like apples or bananas. Bananas are particularly good. And some minerals as well. But also just normal snacks that you like to eat. Gels are good to keep with you in case you make a mistake with your fueling and have a sugar flat.”

Tip 2: “Know the course” — “You should reduce the pace by 3-4 kilometers per hour, or even 5 depending on the course. And to know how to pace yourself, you should analyze the course along with the weather forecast. Why? The weather forecast will say that the wind is coming in one direction, and that will have an impact.

“You need to know if you have to put more energy in the beginning, or wait and keep some energy for the headwind at the finish. Divide the ride into substages, and then have a clear plan for each. For example, ‘This section will be hard because it’s a five-kilometer climb, so I have to arrive here with enough drink and food because I’ll need to have energy available.'”

(If you, too, are targeting the Trek 100, you can preview your route and download course maps here. Very handy!)

Tip 3: “Be aware of heat” — “The other thing is heat stroke. That’s something we can see in the popular marathons, and we see it when people go in with under-training when the weather conditions are warm.

“I have one close friend who finished in the hospital because of heat stroke. It can happen. It’s something you think happens to other people and not to you, then suddenly it’s closer than you think.”

So that’s it! Very easy and straightforward.

OK, sorta. There are a few considerations to make before rolling up to the startline of the Trek 100 or whatever your century ride of choice. But again I must stress that if experienced riders think a dummy like me can do it, there’s a good chance you can too.

Training doesn’t have to be complicated. As our good friends at TrainingPeaks explain, every program is roughly a cycle of overload, progression and recovery. And if you feel unsure of yourself, or daunted by the prospect of training, just remember that step one never changes:

- Ride bike.

That’s it. Get going.